Maheov, Tommy Orange

“Maheov”

Martin was a miracle baby like Jesus. His parents named him god but they hid it in the middle with purposeful inexactitude. Also he was a twin and they both would have had the middle name god, but Martin’s brother died when their mom was having them. All he ended up being called was: the one they lost. They had medically sterilized Martin’s mom, which means they tied her tubes was how she told him. Which was how he was a miracle baby, and maybe even twice over because of what happened to the one they lost.

Martin’s family is Cheyenne, Cheyenne and Arapaho enrolled, but Southern Cheyenne through and through. To further keep Martin from the embarrassment of having god as a middle name, his parents named him Maheov instead of Maheo—the Cheyenne word for god. Maheov was the Cheyenne word for the color orange, which was different from the Cheyenne word for the fruit. Maheov was really just the Cheyenne words red and yellow put together into one word, just like the colors red and yellow together made orange. The secret about them meaning god for him and not the color orange was kept like the secret about his mom being medically sterilized to stop the spread of their kind, their kind of people, that’s actually what the Cheyenne word for themselves meant, going way back, according to Martin’s dad and a book he made Martin read over and over, written by their relative Henrietta Mann about the history of Cheyenne experience in education systems which was really just about the only history book about their kind of people written by one of them. Martin homeschooled his whole life on account of his parents not believing in what they were doing in the schools, what they were teaching and how they were teaching it, especially regarding the history of Native people in this country, and most especially regarding Cheyennes.

Homeschooling was hard, and meant Martin didn’t have friends like he could only imagine he would have had being in school together all the time and having private jokes and games between classes and knowing just how other kids ran when they were scared of being tagged or what they smelled like at the end of the day or how they might make fun of any of his names the way he’d seen in movies kids make fun of names so much in school. The only time his parents ever used Maheov was if he was in trouble and when that was the case it was Martin Maheov, his first and middle names together calling him into the kitchen or the living room whenever he did something they said he shouldn’t or didn’t do something they said he should.

The only way Martin had friends was from going to Native American Church meetings on the weekends, which meant driving up north an hour and staying up late with kids he might never see again while their parents ate peyote and prayed all night to Maheo or whatever other names for god they might have used depending on where they came from. Actually there tended to be a lot of Jewish hippies and in that case it was haShem, which wasn’t their name for god but just meant the Name; and then of course there was Jesus or whomever non-Jewish white hippies prayed to, the Universe or whatever. Mostly playing with the kids he played with meant playing video games or telling scary stories or listening to the big boom of the kettle drum from inside the house wondering how their parents could stay up and sing and pray for so long when they were kids and could barely make it past 2:00 a.m. with soda and video games and on this one night a joint. This was the first time Martin smoked anything more than a cigarette, and while he was nervous, it felt natural, to be trying drugs out, like the beginning, because knowing your parents did drugs regularly, and having it be a part of their religion, did something to the way Martin thought about that joint when it was passed to him. All of which ended up making what ended up happening this one night even crazier than it already was.

They were asking one another about their respective middle names because they were bored and it was super late and there was nothing else to talk about. These kids’ names were Seth and Micah, with middle names like Jacob and maybe Esau, which seemed normal enough, but not more normal than Martin. When it came to his middle name, he could have stopped at it being the color orange in Cheyenne or the colors red and orange put together in Cheyenne but it was late and they’d smoked that joint and you want to have something to talk about in these kinds of situations so he told them his mom wasn’t supposed to be able to have babies after being medically sterilized, and that he was a miracle baby like Jesus.

“What’s sterilized mean? I thought it was like, for strength, like for muscles and sports or whatever,” Micah said.

“He said sterilized, not steroidized,” Seth said, glaring. The glow from his phone on Micah’s face meant he was looking up what sterilized meant.

“Wait, so they gave you the middle name god because your mom got sterilized but then had you anyway, even though she wasn’t supposed to be able to have babies?” Seth asked.

“It’s stupid. I don’t actually know what the chances are that sterilization doesn’t work. Anyway, doesn’t Jesus mean like a whole different thing for you guys, like for Jewish people?”

“Jesus is cool,” Seth said, “but he’s not like, our guy.”

“You know all those ideas about genocide and sterilization Nazis used on Jews they got from what the US did to Native Americans?” Micah said, looking at his phone.

“I homeschooled and both my parents are Native, so like, yeah,” Martin said.

“Who do you think the American version of Hitler would be if you had to name one guy?” Seth asked. Martin was about to say Andrew Jackson when he heard yelling outside the window. It was the first time he’d gotten high, and the first time his middle name being god came up with anyone outside of his family, but what made the night memorable was what they watched below—one of the hippies came running out fully on fire and screaming. Martin’s dad was trying to put him out with a blanket but he kept yelling that it was god. That it was all god. And it went on like that for he doesn’t remember how long, but it seemed like forever, the hippie yelling that all of it was god, Martin’s dad trying to put him out with the blanket.

On the way home the next day his dad told him they found out the guy had taken acid before the meeting. That he wouldn’t be welcomed back into ceremony. When Martin asked if he’d be OK, neither of his parents answered. So he asked his mom how they could do that kind of medical procedure on her without her saying it was OK. There was a long silence, at first probably because it seemed to have come out of nowhere, and then because it was the kind of question that required more than an answer could give. The sound of the road seemed like it was blaring, like music Martin wanted to be able to turn down, like sometimes how they’d play peyote music too loud in the car on the way back from meetings. Martin wondered if the loudness had something to do with the joint, with being high, with having been high, which made him wonder how long it lasted, its possible residual effects, and then he wondered if different kinds of drugs reacted to each other so like the high of being high from weed and the high of being high or having been high from peyote would those two things together do something else? There clearly was something more still happening to his thinking, he was thinking when his mom finally answered his question.

“White people been thinking they were the better people all along and that progress and civilization means making more of themselves in the world, and making sure less like us make it through. You can see it in movies and books and in every way we never get to be seen the way we really are. And then what little of us gets allowed through is always the same dumb thing,” his mom said.

“But they really didn’t tell you they were doing it, the sterilization?”

“You found a way through. That’s what matters. That we keep making our way through.”

“Are Jewish people white?” Martin asked. His mom looked at his dad, then back at him in the rearview mirror with a kind of pained squint Martin couldn’t decipher, then back to his dad in this like “aren’t you gonna say something” kind of way.

“It’s not that all white people are bad,” his dad said.

“But are they white?” Martin asked. “Jesus wasn’t white, and he was Jewish,” his mom said.

“Why was that guy on fire saying it’s all god?” Martin asked. And then, before they could answer, he thought about if he was high and also maybe their highs were reacting to his high. What did any of that mean and was it OK? He knew he was acting different, asking more than he normally did, this time in the car would usually have meant them singing along to their peyote tapes, Martin staring out the window at the way back home, but he couldn’t help the way he was thinking and especially help that he kept wanting to ask these questions. “Why are drugs like acid bad and peyote’s like, spiritual, or like medicine or whatever?”

“Most drugs aren’t inherently bad, it’s the way people use them. The kinds of people they already are can come out on drugs in ways that can be bad, can hurt people,” his dad said.

“I smoked weed last night,” Martin said, not right away feeling nervous about it, which felt weird, and then when no one said anything for a while he did get nervous, and the loud road blared again. Martin knew his question was being weighed against their use of peyote, and what happened with the crazy hippie on fire, and his confession about smoking weed. He also knew that now they knew about him acting different than normal, asking these questions, and he wished he hadn’t told them about getting high, because it might diminish their sincerity, make them act like oh this is just a part of the kid getting high for the first time, instead of taking his questions seriously, which, he felt, he didn’t have more serious questions than these.

“Did you like it?” his mom asked.

“It was OK, until that guy came out of the teepee on fire. I mean we laughed hella hard together, me and Seth and Micah, we cracked up pretty hard for a while because it was so crazy. Then after seeing dad trying to calm him down and put him out, it stopped being funny and got hella sad. I had told them about being named Maheov and, like, the miracle baby thing, you being medically sterilized, we’d just started talking about it all before the guy came out of the teepee on fire, so then that was like, hanging over me, and they both said they were going to bed kind of suddenly, and I was high and couldn’t sleep and felt really scared about a lot of things I can’t remember anymore. I’m not trying to smoke weed again any time soon if that’s what you’re worried about.”

Martin’s mom and dad both laughed. And he laughed with them. But then it was just like that night when Micah and Seth went to bed. It didn’t feel like there was anything to say, or like nothing more could be said about what they were talking about. The road got loud again. Then his parents turned their peyote music up too loud. And the years after that felt blurry to him, like that was the beginning of the end of something in him that he can’t remember. They didn’t bring him to meetings anymore after that. Then they divorced and his dad moved back to Oklahoma. It was pretty sudden but afterward and especially looking back somehow felt inevitable. About a year after the divorce his mom had a meeting for him, for the family, and Martin ended up at that same house with Seth and Micah in the meeting with them. He was pretty scared to take the medicine. To do drugs like that. But he was with his mom and it felt like she really needed him to be doing that with her. Martin caught eyes with Micah and Seth when the effects of the medicine first started coming on. He almost lost it, almost laughed about the hippie on fire. Later in the night he heard his mom praying about their kind of people, about his dad back in Oklahoma; she was asking god to do what needed to be done to make things as they should be, which to Martin felt almost like saying nothing to god, like saying god do your thing.

But later that night, or early the next morning, he got it. Even about what that hippie could have been thinking, staring into that fire, everything god, and he thanked everything he felt god to be in that moment like he’d never said thank you to anyone. He got way down in his prayer, bent over on his knees. He thanked the journey through tubal ligation and twin sibling death to get to where he could be alive thinking about it all, thanking it all. Martin understood the wisdom that made it medicine, and how stupid he’d probably always be after moving away from that singular moment of understanding and gratitude, which created something in him that he would chase the rest of his life, which wasn’t a bad thing to chase, but it sure did end up hurting to hunger for.

_________________________________

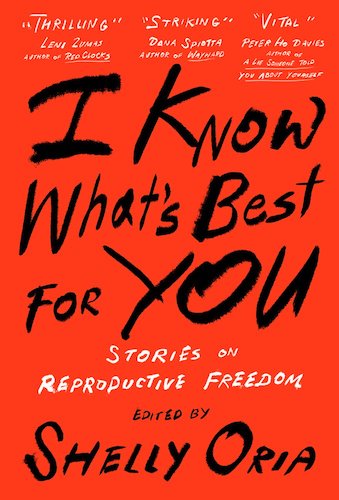

“Maheov” from I Know What’s Best For You: Stories on Reproductive Freedom, edited by Shelly Oria. Reprinted with the permission of McSweeney’s. Copyright (c) 2022.

Comments

Post a Comment

Please leave a comment or use the contact form (which is private)