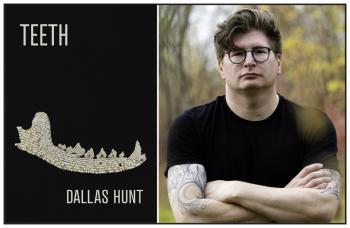

Teeth | Dallas Hunt (Cree)

New poetry collection breaks free of limited Indigenous narratives

Dallas Hunt’s latest release is a book of poems exploring ideas of urban Indigeneity, decolonial theory and how First Nations find ways to create and continue to exist.

Hunt, a member of Wapsewsipi (Swan River) First Nation, said his new collection Teeth sets out “to challenge the expectations and stereotypes placed on Indigenous writers.”

Writing has always called to Hunt, he said, and he was encouraged by teachers and his family.

While his childhood had its tumultuous moments, his kôhkom (grandmother) and mom “really had a knack of finding a way when things were particularly hard or difficult. They would still find these little pockets of livability for me and my siblings and my cousins where we could nurture and cultivate these spaces,” he said.

“Where we could read, write, laugh and express all the things, responses to what we were encountering, but also all the joyous moments.”

Hunt has earned a Ph.D, and teaches at University of British Columbia. He said it was when he needed a break from academic writing that he returned to his creative writing.

His books range from an award-winning children’s book Awâsis and the World-Famous Bannock to non-fiction with Storying Violence: Unravelling Colonial Narratives in the Stanley Trial , which is about the Colton Boushie’s killing in Saskatchewan, co-authored with Gina Starblanket.

Hunt’s first collection of poetry, Creeland, was nominated for the George Ryga Award for Social Awareness in Literature, the Gerald Lampert Memorial Award and the Indigenous Voices Award.

The title of the new collection came from noticing that ideas about teeth were rising up in several of his poems. In his poem “Maskosiy” for example, Hunt writes “I wanted teeth that were a map of the world.”

The cover art for Teeth features a jaw beaded by his cousin, artist Michelle Sound, inspired by Hunt’s original vision of a fox’s jaw—glowing beads against beads of varying shades of pearl, ivory, smokey and ghost white.

They worked on a few drawings before circling back to Hunt’s original vision of a fox’s jaw—glowing beads against beads of varying shades of pearl, ivory, smokey and ghost white.

Hunt uses his poetry to highlight “symptoms of colonization” and the power imbalances that persist and the systems that maintain inequities, he said.

He finds ways to communicate private emotions and collective struggles with narrative poems in which he layers the Cree language. There are dreamlike passages and even the use of professional wrestling figures to explain concepts like the opinion that “commerce makes heels of us all.”

Creeland was more direct, Hunt said of his previous poetry collection.

“I feel like a lot of this (Teeth) collection is a little more oblique. I'm trying to arrive at less of a thing, a concrete object or idea, and more how an object might make me feel or other people feel.”

Hunt departs from obliqueness with "There's a Poem for Everyone”, which addresses the narrow frames and limited narratives often imposed on Indigenous peoples, like the way “pigeonholed Indigenous writers” are expected to stick to the script of “romanticized Indigenous people's writing about nature,” he said.

“It always has to be this glorious celebration of the natural world,” he said. “There is a sort of desire for Indigenous peoples to always be writing about berry picking or moose meat or a very limited set of frames.”

“And yes, we admire the territories we come from, or our environment, but we also struggle with it and we're in relation to it. And sometimes that can look incredibly joyous and great and generative, and other times it's difficult and it is a struggle, but we're still in relation,” said Hunt.

“I think sometimes words like relationality and kinship float around that people glom onto.” Hunt said Cree kinship is about the act of relating, and “relation is not static. It doesn't look the same across and over time and it doesn't look the same all the time, but rather it changes. It fluctuates.”

Along with countering stereotypes, Hunt follows with a larger question: “What sort of narratives might be possible for Indigenous writers if we weren't circumscribed by this desire to be legible or palatable to particular audiences?”

“In order to really speak to the ways that we engage with our relations, and that includes the earth itself in our relations and our other-than-human kin, we should be attentive to the full range of emotions or ways of relating that might be at play or at work in our everyday lives.”

For Hunt, poetry is a place to work through larger questions and “sometimes I'll write something and I'll say, ‘okay, I've expressed what it is that I was thinking’, or ‘I've been able to articulate a problem or a potential solution to a problem that I've been struggling with’,” he said.

“And for whatever reason, poetry or poetics was the way that I could arrive at that place. And we sometimes think of this as a solitary act.”

He has heard from people that his poems help them express a feeling. For example, in the poem “Dim,” he writes, “To love the light so much, you’d tear yourself into two,”.

“I've had people say that my poetry has helped them articulate something that they had trouble articulating before. That's always very heartening to me. And it's not something that I ever have in mind while I'm writing,” Hunt said.

“I’m just shocked when people say things like that to me, really. I'm also thankful.” He said he “starts to realize it’s not just me in a dark room writing something, but rather other people engage with it, and it has effects on them. It means a great deal to me.”

Teeth is published by Nightwood Editions. It can be order here: https://nightwoodeditions.com/products/9780889714526

*

Comments

Post a Comment

Please leave a comment or use the contact form (which is private)